Consumption of plant nitrates has a good impact on blood pressure and incident cardiovascular diseases.

See here for a brief summary of a Danish study on diet, cancer, and health. (1)

The vascular effects of inorganic nitrate, observed in clinical trials, translated into a reduction in cardiovascular disease (CVD) with usual dietary nitrate intake in prospective studies, therefore warranted investigation. They sought to determine whether plant nitrate, the major source of dietary nitrate, is associated with lower blood pressure (BP) and a lower risk of incident CVD. Among 53,150 participants without CVD at baseline, plant nitrate intake was assessed using a comprehensive plant nitrate database. During 23 years of follow-up, 14,088 incident CVD cases were recorded. Participants who consumed the highest number of plant nitrates (median, 141 mg/day) had 2. Compared with participants who had the lowest intake (median, 23 mg/day), moderate intake of plant nitrates (median, 59 mg/day) was associated with a 15% lower risk of CVD.

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the association between plant nitrate consumption and incident CVD in the Diet, Cancer, and Health Study cohort. Plant nitrate was the focus of attention because approximately 80% of total dietary nitrate intake comes from vegetable consumption.

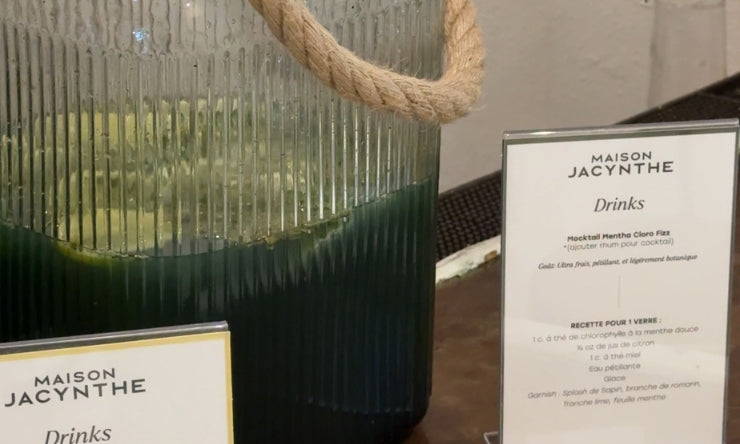

Note that the main food sources of nitrates are vegetables; among those containing the highest levels of nitrates are: arugula, spinach, lettuce, radish, beetroot, Chinese cabbage.

In this study, an inverse association was observed between plant nitrate intakes, up to 60 mg/day, and CVD hospitalizations. Specifically, moderate to high nitrate intakes were associated with a lower risk of IHD, ischemic stroke, PA, and HF. Higher plant nitrate intake was also associated with lower SBP and DBP. The results suggest that ensuring the consumption of nitrate-rich vegetables, corresponding to approximately 1 cup of green leafy vegetables, may reduce the risk of CVD.

Fruit and Vegetable Consumption – Impact on Stress, Mood, Sleep

First, here is a study from Australia published in April 2021 (2) and carried out with the main objective of exploring the relationship between fruit and vegetable consumption and stress in a group of men and women aged 25 and over. This group had to complete two questionnaires, one on their dietary intake of fruits and vegetables and the other on perceived stress during the same period

Result: Among Australian adults, higher FV consumption was associated with lower perceived stress, particularly among middle-aged adults. These findings support current recommendations that fruits and vegetables are essential for health and well-being.

A second repeated study in five waves (3) , this time among Canadians (n=296,121 aged 12 years or older), was conducted between 2000 and 2009. The primary outcome measure was a major depressive episode in the previous 12 months. Logistic regression models adjusted for age, sex, household income, education, physical activity, chronic diseases and smoking.

The aim was to also examine the association between the frequency of fruit and vegetable consumption and mental health disorders.

Results: During the first wave, fruit and vegetable intake was higher while being associated with a lower likelihood of depression. Those with the lowest dietary intake were significantly more likely to experience distress. All of these results were similar across the other four waves. Poor perceived mental health and a previous diagnosis of a mood disorder and anxiety disorder also demonstrated statistically significant inverse associations with fruit and vegetable consumption.

A third study (4) , this time in 171 young adults, to test for 14 days, during a clinical intervention, the psychological benefits vs increasing the consumption of fruits and vegetables.

Participants were randomly assigned to a usual diet control condition, a momentary ecological intervention condition involving text message reminders to increase their fruit and vegetable intake plus a voucher to purchase fruits and vegetables, or a fruit and vegetable intervention condition in which participants received two additional daily servings of fresh fruits and vegetables to consume in addition to their normal diet.

Before and after the intervention, self-reported outcome measures were depressive symptoms and anxiety, as well as daily negative and positive mood, vitality, and fulfilling behaviors (curiosity, creativity, motivation) assessed each evening using a smartphone survey. Vitamin C and carotenoids were measured from blood samples before and after the intervention, and psychological expectancies regarding the benefits of fruit and vegetable consumption were measured after the intervention to test as mediators of psychological change.

Only participants in the extra fruit and vegetable condition showed improvements in psychological well-being with increased vitality, fulfillment, and motivation over the 14 days compared to the other groups.

The study concluded by stating that providing young adults with a supply of high-quality fruits and vegetables, rather than reminding them to eat more fruits and vegetables (with a voucher to buy fruits and vegetables), led to significant short-term improvements in their psychological well-being.

A fourth study (5) over a period of 3 months on young adults who were low consumers of fruits and vegetables (less than 3 portions/day), in order to see the link between the consumption of fruits and vegetables and insomnia, quality and duration of sleep.

They categorized changes in fruit and vegetable consumption into four categories: no change or decrease, 1 serving increase, 2 serving increase, and 3 or more serving increase. They then compared changes in chronic insomnia classification (yes or no), sleep duration, quality, and time to fall asleep (all self-reported) across fruit and vegetable change categories. Analyses were both overall and stratified by sex, adjusting for potential confounders.

The following results were obtained: Mean ± SD age was 26 ± 2.8 years (71% female). At 3-month follow-up, participants increased fruit and vegetable consumption by an average of 1.2 ± 1.4 servings. Women who increased their fruit and vegetable consumption by more than 3 servings showed improvements in insomnia symptoms (2-fold increased odds of improvement; 95% CI 1.1 to 3.6), sleep quality (0.2 point higher sleep quality score; 95% CI -0.01, 0.3), and time to fall asleep (4.2 minutes; 95% CI -8.0) compared with women who did not change or decreased their fruit and vegetable consumption. The associations were not as apparent in men. They concluded that young women with low fruit and vegetable intake may experience improvements in sleep difficulties related to insomnia simply by increasing their consumption.

Here is another study on the impact of eating strong, bitter-tasting vegetables versus mild, sweet-tasting vegetables. (6)

A recent 12-week controlled study was conducted in 92 type 2 diabetics who received 3 different types of diets. Group 1 was instructed to ingest: 500 g of strong and bitter tasting vegetables; group 2: 500 g of mild and sweet tasting vegetables; and group 3: 120 g of mild and sweet tasting vegetables.

Both plant-based diets contained root vegetables and cabbages selected based on sensory differences and phytochemical content. Before and after the study, all participants underwent an oral glucose tolerance test, 24-hour blood pressure measurements, DEXA scans (fat mass, lean fat-free mass, bone mass), and fasting blood samples. Both plant-based diets significantly reduced BMI, total body fat, and HbA1c levels compared to the control, but in the strong-bitter vegetable group, significant differences were also found in the 240-min incremental area under the glucose curve (OGTT) and fasting glucose levels. However, the strong-bitter vegetable group had a greater impact on insulin sensitivity, body fat, and blood pressure compared to the other groups.

References:

(1) Translation of the article Vegetable nitrate intake, blood pressure and incident cardiovascular disease: Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Study https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10654-021-00747-3#Tab1

(2) Fruit and vegetable consumption is inversely associated with perceived stress throughout adulthood Published: April 09, 2021: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2021.03.043 https://www.clinicalnutritionjournal.com/article/S0261-5614(21)00192-8/fulltext

(3) The association between fruit and vegetable consumption and mental health disorders: evidence from five waves of a national survey of Canadians PMID: 23295173 DOI: 1016/j.ypmed.2012.12.016 Prev Med. Mar 2013;56(3-4):225-30

(4) Let them eat fruit! The effect of fruit and vegetable consumption on psychological well-being in young adults: A randomized controlled trial. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28158239/ PMID: 28158239 PMCID: PMC5291486 DOI: 1371/journal.pone.0171206

(5) Changes in fruit and vegetable consumption in relation to changes in sleep characteristics over a 3-month period in young adults https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2352721821000139 ,

(6) Strong and Bitter Vegetables from Traditional Cultivars and Cropping Methods Improve the Health Status of Type 2 Diabetics: A Randomized Control. Reference: Thorup, AC; Kristensen, HL; Kidmose, U.; Lambert, MNT; Christensen, LP; Fretté, X.; Clausen, MR; Hansen, SM; Jeppesen, PB Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1813. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061813

Leave a comment